What Was the Forge? – Tabletop RPG Design in Theory and Practice at the Forge, 2001-2012: Designs and Discussions

Jukka Särkijärvi

Some years ago, tells William J. White, he was sitting at a Persian restaurant during a gaming convention in Morristown, New Jersey. He was accompanied by a friend, indie role-playing game designer Michael Miller (FVLMINATA), who said that people are forgetting the Forge.

Instead if being quietly grateful, White decided to write a book. Tabletop RPG Design in Theory and Practice at the Forge, 2001-2012: Designs and Discussions is, like Nick Mizer’s book I read a while back, an instalment of Palgrave Macmillan’s Games in Context series and a Serious Academic Book. White is a Professor of Communication Arts and Sciences at Penn State University and has published role-playing game studies here and there. He was also a Forge user himself and released the role-playing game Ganakagok in 2008.

But the Forge. Why was it necessary to write a book about some online forum?

I’ve actually been wondering for a while now, why aren’t there more of these.

History

The purpose of the Forge was to be a space for analytical, theoretical discussions of role-playing games, their design, and publication. Compared to other online forums of the time, it was hyperfocused, and there was no room for off-topic chit-chat. It is strongly personified in its founder Ron Edwards – a book about the Forge cannot help but also be a book about Edwards – and is most often remembered for a theoretical model about the creative goals of role-playing games called the GNS Model. Elsewhere on the gaming internet, the forum quickly acquired a reputation for elitism and incestuousness.

Of course, the context is the early 2000s when the gaming internet was even more unbearable than it is today.

The Forge, however, was not only a venue for para-academic egotripping. It was born during a sea change, when the PDF became more common as a format, and the rise of PayPal made selling stuff on the internet easier for smaller publishers. Forge’s strictly analytical discussions and theoretical formulations bore fruit, and the community produced many innovative new games. The first of these was Edwards’s own Sorcerer, which actually predates the Forge by a few years. One of the Forge’s formative events was the founding of Hephaestus’s Forge, a forum started up by Edwards with Ed Healy in 1999, which was up for some months. In his own words, Healy put the forum up in order to get Edwards to fix Sorcerer up into a proper game publication. Instead of talking theory, Hephaestus’s Forge’s purpose was to assist people in getting their own games published. It collected Edwards’s essays about publishing games and also other resources, such as links to places that supplied you with ISBN numbers (which in Finland is trivial and in the U.S. complicated and expensive). After Hephaestus’s Forge went offline, Edwards started up a new forum by the same name together with Clinton R. Nixon (The Shadow of Yesterday). The name quickly became just “The Forge”.

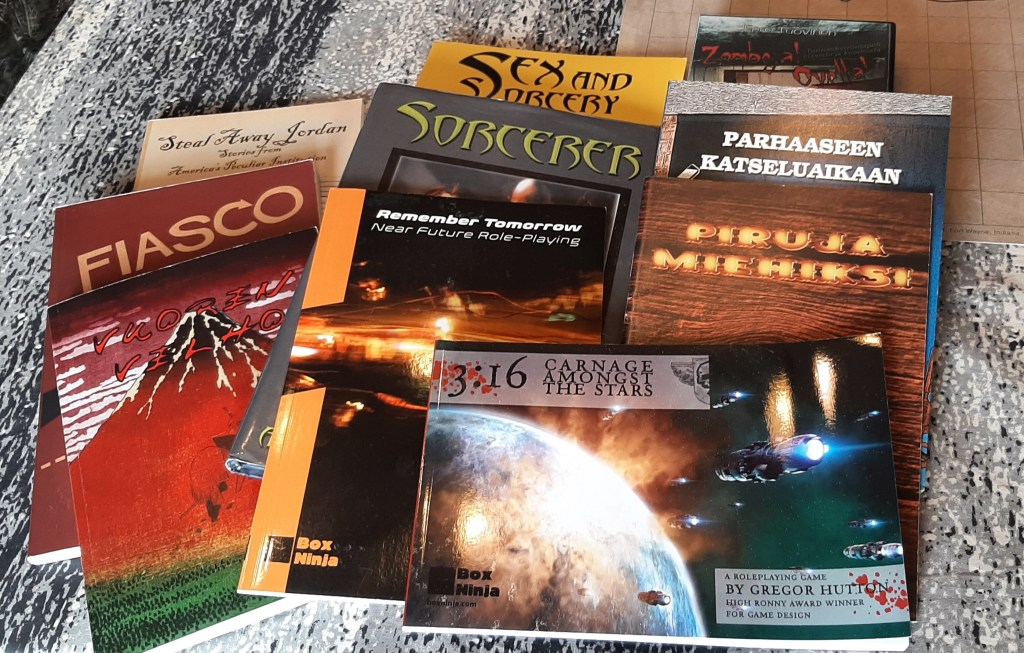

In 2001, Edwards started up Adept Press and published Sorcerer. It won the Diana Jones Award for Excellence in Gaming in 2002. More games followed. Forge’s classics include, among others, Paul Czege’s My Life with Master (2003), Vincent Baker’s Dogs in the Vineyard (2003), Jason Morningstar’s Grey Ranks (2007) and Fiasco (2009), and many others. Back then, small publishers’ options for distribution were limited and the big game wholesalers didn’t pick up just anyone’s books. For this, Indie Press Revolution was founded in 2003. Many publishers were also apprehensive about selling PDFs on the then-new RPGNow storefront, fearing it would feed piracy. In Finland, the publisher Arkenstone took up local distribution and also released several Forge games in translation. White discusses also the Forge Booth, an sales booth for all indie role-playing game publishers at Gen Con, its sales techniques, and its history. Games on Demand, a feature of Finnish conventions, was originally developed at the Forge Booth.

At the Forge, they talked about games, designed games, critiqued games, analysed gaming, and discussed theory. Then, in 2012 Ron Edwards declared that the forum had fulfilled its purpose, locked it down, and that was that.

Opening the Time Capsule

White’s book goes over all this history leaning on interview materials collected for the book as well as Forge’s own message archive. Though posting on the Forge is no longer possible, the forums are still available to read, and to a patient researcher they are a treasure trove. In addition to delving into the contents of the posts, White uses the forum threads to analyse the social dynamics of the Forge. When Ron Edwards guides a new user to analyse their own play and to consider what they want out of their games, he presents as a fatherly guru.

In addition to being a guru, Edwards was also a game designer, one of the leading lights of the indie role-playing game movement, and on top of that the forum’s owner and moderator, which was not an unproblematic combination. In his own words, Edwards did not believe in banning disruptive users, because they would hold it as a badge of honour and go brag on other forums, all the while ignoring that this allowed them to continue disrupting his own forum. Edwards did recognize the trolling behaviour and its effects on the Forge, but responded by reorganizing the subforums and closing the theory forum in 2005. This caused bad blood among both Forge users and the users of other forums, who had to suffer from the theory forums’ status games spilling over on their discussion sites. Apart from this, White sees the Forge’s stated moderating policy to follow the common features of healthy online communities.

The book also delves deep into Edwards’s biggest mistake, his 2006 declaration that older role-playing games, especially of the World of Darkness family, have made their players unable to create stories, using the phrase “brain damage”. White analyses the thread and later instances where Edwards, holder of a PhD in zoology, repeats the claim, and presents Forge games as prosthetics of a sort to enable these disabled players to once more tell stories. White and his interviewees speculate as to why Edwards decided to die on this hill, but the only thing certain is that it is still remembered.

White also gives voice to women and racialized people – unlike the Forge often did. The forum’s pseudointellectual, white American masculine atmosphere was felt to be exclusionary, and problems were downplayed. As a contrast, game designer Emily Care Boss (Romance Trilogy) presents the Usenet group rec.games.frp.advocacy, where several of the core userbase were women. Julia Bond Ellingboe (Steal Away Jordan) tells of the backlash she got over her slave narrative game, drawing from her own family history.

In the end, though, the community of the Forge was closed to nearly everyone who was not there at the beginning. The old guard was very resistant to explaining things and questions often received the response of “Go read the threads”. This was a threshold that kept rising as the mass of text accumulated. Even Edwards’s own essays were just the starting points for further discussion that refined the thoughts.

That Theory, Though

Unfortunately, we cannot discuss the Forge without discussing the GNS theory. It is a theory based on the older Threefold Model, which was discussed on Usenet in the 1990s and was refined in Edwards’s 1999-2004 essays into “the Big Model”. It sought to express and classify people’s motivations for playing role-playing games and to aid in understanding what role-playing even is. The abbreviation GNS comes from Gamism, Narrativism, and Simulationism, the three different creative agendas, or motivations for play. Although the Big Model has more things in it, most of the theoretical arguments centred on these three and whether something is Gamism or Simulationism and what Simulationism even is, and so on, ad nauseam.

White covers these theories, the discussion, and the nine counterarguments that he considers most significant. These he describes and, in some cases, also attempts to debunk. There are many critiques – it is inaccurate, it ignores immersionism, Simulationism is valued as a lesser agenda, it certainly does not fulfil the requirements of a scientific theory, and so on.

The actual value of Forge’s theory is really in the practice. A central quirk of the Forge’s culture was argumentation by game design. My Life with the Master was a refutation to Greg Costikyan’s claim that making a game more like a story made it a poorer game. Vincent Baker has described game design to be his mode of debating. Sorcerer is very open about being an argument in the favour of a specific philosophy of game design and publishing – and against another philosophy. Epidiah Ravachol (Dread) says: “I will temporarily adopt any bullshit concept about what a game should do, and see if I can build a game around that, and see what that game does then, and enjoy that, where back then, the way to do that, the way to get the energy or the fire, was to say that your paradigm is true, and I will prove it. “My paradigm is true and I will prove it,” like, “GNS is wrong, and I will show you in a game.” If the game you created is good, it doesn’t matter if you’ve proved GNS is wrong, or whatever.”

This was very fruitful for new avenues of thought and game design, and the designers at the Forge developed numerous techniques and mechanics for things like directing the dramatic arc, or developing the themes of a story. The conceptual forebears of many modern games like Apocalypse World and Blades in the Dark were born in its fires.

Designers & Discussions – A Forge Game about the Forge

And just as I got done last time reporting about the OSR monster in Nick Mizer’s book as a big deal, White raises the stakes by putting in an entire role-playing game. Designs & Discussions: An RPG About the Indie Scene is a historical role-playing game that presents an argument about what the Forge was like.

I tested it out.

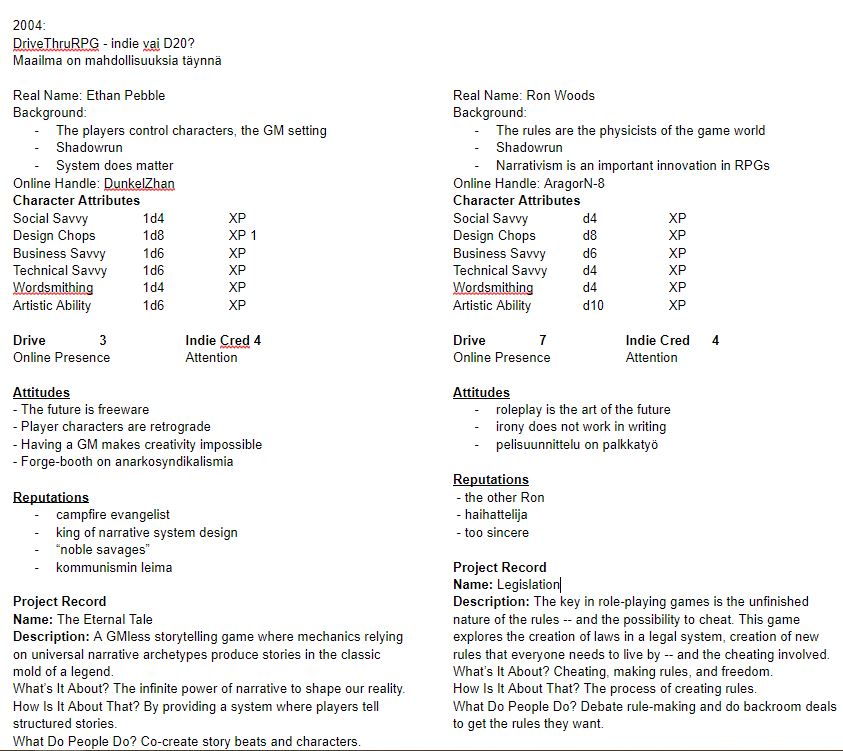

At the start of the game, you determined its historical context somewhere in the years 2000-2012. There is a table that gives some major events for each year in role-playing games, pop culture, the internet, and development of game publishing. The example of play kicks off in 2000, but we felt it’d been seen already and started in the year 2004. A few key things about the year were given prominence, much like the aspects of FATE.

The characters are designers and forum users in the indie role-playing game scene. They hold certain beliefs about both traditional and indie role-playing games, and a play history with traditional games. These are all rolled from tables. In addition, they have certain attitudes, Drive, and Indie Cred. This latter value starts at 3 if the character presents as a straight, white cisman and drops by one for each deviation from this norm, illustrating structural injustice. The characters also have skills like Social Savvy, Design Chops, and Wordsmithing, which is what you ultimately use to make games. These skills are expressed as dice in the full range of Platonic solids, which leaves out the ten-sided die of the classic RPG dice set. In certain circumstances, you can raise your skill values by steps of two: d8 → d10 → d12 → d14, but dice that are not Platonic solids are rolled as the next lower Platonic solid. Dice from 14 to 18 are all d12 in practice.

The game advances in turns that have two phases and last for weeks or months of game time. The first phase is the posting phase, where the characters write forum messages and respond to each other. This is when they create, spend, and earn the metacurrencies of Online Presence and Attention and use skills to shape the discourse and even adjust the attitudes and reputations of their own or other characters.

Rolling a one always results in a kerfuffle, an obstacle valued at half the die rolled. Most of these are different types of forum blowouts but there is also the possibility of financial loss and system crash. This must be removed by either accepting reputations from other players or by burning Attention or Drive. Neutralizing kerfuffles is expensive and bad luck can easily burn out the characters. The angry internet has no mercy. The GM holds no moderating tools for the forums.

The second phase is for game design, when the players advance their game projects by rolling their skills to develop their content, form, and marketing. If the result is not a one or a prime number, the project is as good as it’s ever going to get in that area. If a part of the project reaches a number that is a square or a cube, the character gains experience points.

At the end of the turn, you check if anyone finished a project and roll for whether the experience taught them anything. Then you start a new turn.

The fun part of the game is coming up with over-the-top forum posts and operating your bullshit generator at full energy. The game projects as arguments supporting these overblown forum messages pretty much write themselves afterwards.

Designs & Discussions is White’s closing argument about the Forge. This was the game they played. It was not balanced, its rules were often illogical and arbitrary, and it burned through player characters at an alarming rate.

When the human cost was not too high, games were born.

The Forge’s Fire is Ashen-Cold

The book began with the forgetting of the Forge. This is true. Against this background, White’s book is among the more valuable works of role-playing game scholarship, and the most important book documenting the Forge’s its community, and their thoughts.

In fact, it is the only book about the Forge, which is symptomatic of the problem. The Forge’s Achilles heel was always documentation. “Go read the threads!” echoed across the forums and drowned out calls for approachable summaries. The most significant source of the theory chapter is not a Forge essay or a thread but Emily Care Boss’s article in Playground Worlds, published in 2008 at the Solmukohta larp conference in Finland, edited by Markus Montola and Jaakko Stenros. Their arguments were in the games, but as compiling this text showed me, many central titles are poorly available. Old webstores are full of dead links and broken image files. My Life with the Master doesn’t exist even in the creator’s own storefront. Riddle of Steel is no longer for sale. Montsegur 1244 and Kagematsu seem to have vanished. Many games are only available from their creators’ own storefronts with oft-dubious payment options. (Translator’s note: when this article was first written in 2021, the situation was significantly worse but has since improved.) The trailblazers have been left behind.

The Forge is being forgotten.

What are we losing?

This piece was first published in Finnish at roolipeliloki.com, on April 20th, 2021. Translated by the author.